Chapter 4 - Longevity interventions and models

Contents

Chapter 4 - Longevity interventions and models#

We need a way to classify all of the therapeutic interventions. Here we will outline interventions, pathways and organisms that have been shown to be relevant for aging.

Contents of this chapter are:

Molecular pathways involved in the aging process.

Chemical basis for longevity.

Environmental basis for longevity.

Alternative (less known and researched) longevity interventions.

Model organisms of aging and its alternatives.

Molecular pathways involved in the aging process#

A biological pathway is a series of actions among molecules in a cell that leads to a certain product or a change in the cell.

In cells, there exist defined ways in which proteins react with each other in many ways: Proteins can combine to form larger structures, they can change conformation (shape), react to split into smaller proteins, etc. These usually happen in defined networks, or pathways, which can also feature loops, causing negative or positive feedback, enabling various forms of homeostasis.

Here you can see a map of the proteins that are involved in regulating longevity, and their interactions.

Examples of pathways known to have effect on longevity.

1. mTOR/AMPK

2. IGF-1/PI3K/FOXO

3 .Klotho and NRF2

4. Sirtuins

1. mTOR/AMPK

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), also referred to as the mechanistic target of rapamycin, and sometimes called FK506-binding protein 12-rapamycin-associated protein 1 (FRAP1), is a kinase that in humans is encoded by the MTOR gene. mTOR is a member of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-related kinase family of protein kinases.

The AMP-activated protein kinase AMPK acts as a cellular energy sensor. Once switched on by increases in cellular AMP : ATP ratios, it acts to restore energy homeostasis by switching on catabolic pathways while switching off cell growth and proliferation. AMPK has effect on mTOR, hence on the whole mTOR pathway.

What things are regulated through mTOR pathway?

Translation

Metabolism

Autophagy

Senescence

mTOR pathway, its connections to AMPK, and potential products of up, down regulation:

What is the relevance to longevity?

mTOR activity increases misfolded protein levels, downregulates autophagy and increases aging speed. Hence inhibition of mTOR seems to have implications on longevity.

On the other hand, fasting activates AMPK which downregulates mTOR and with that induces autophagy. With that aging speed decreases. Metformin induces AMPK hence its one of the possible Geroprotectors (more on that in chemistry of ageing)

What is the rapamycin? The most prominent mTOR inhibitor, capable of downregulating its activity hence achieving the desired outcomes in:

Autophagy

Cellular senescence

etc.

2. IGF-1/PI3K/FOXO

There are 2 possibilities (left and right picture) that trigger the IGF-1 pathway. The first one (left) in times of favorable conditions activates the hypothalamus and triggers the release of growth hormone in the blood stream. Which again triggers the production of insulin like IGF-1 in the liver.

Consequence of which is that on the one hand cell growth and reproduction is triggered.

On the other hand it supresses FOXO dependent activation of proteostasis processes. Like the UPS pathway, autophagy and DNA repair. Which we know has consequences on longevity.

In short, if we look at the left picture, the body grows and cell reproduces but the cost is accelarated aging.

On the other hand, if we induce moderate stress as in the right picture, the body will block the production of insulin like IGF-1 in the liver which again in turn unblocks FOXO dependent mechanisms.

3. Klotho

Klotho is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the KL gene. There are three subfamilies of klotho: α-klotho, β-klotho, and γ-klotho.

The way it works, is that underexpression reduces mice lifespan and the overexpression increases mice lifespan.

As visible in the picture, the inhibition or the activation activates the pathways that have lifespan reducing or lifespan expanding effects.

4. Sirtuins and NAD+

NAD+ is a cofactor, or a “helper molecule,” for a large class of deacetylases called sirtuins and PARPs (poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase)

Sirtuins enzymes require a non-protein chemical cofactor like NAD+ to function. The effects of sirtuins go well beyond metabolism. They play key roles in inflammation, transcription of genes, programmed cell death, and — of course — aging.

Different sirtuins are localized differently within the cell and have varying targets.

The sirtuins residing in the nucleus of the cell function as histone deacetylases and are vital for genome integrity and stability. Histones are proteins that DNA wraps around such that only the necessary bits are accessible and the rest is safely packed away. If there is a lack of NAD+, their function is reduced, the DNA loosens, and the histones are exposed to damaging external agents. Protecting genome integrity is essential for every cell to maintain its regular functions and characteristics.

PARPs

Another important family of proteins that require NAD+ are the DNA repairing proteins called PARPs(poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase). DNA damage can accumulate in our cells as we age, and our cells try to do everything in their power to protect their DNA since it is the code book that regulates all life. More damage collected overtime would also require more repair, which is a problem in itself. PARPs similar to sirtuins can also play a role in protein post translational modifications via adding ADP-ribose units to certain proteins, a process called parylation. At the moment, much less is understood about how parylation impacts gene expression and protein function than acetylation/deacetylation, but it is expected that this part of the NAD+ field will grow rapidly in the coming years.

Changing something just in the brain can be enough to make a mouse live longer. If the hypothalamus thinks it is too warm, for example, it can decrease the core body temperature of a mouse, resulting in a slightly longer lifespan. Changing the level of a variety of genes in a brain-specific way can also make a mouse live longer.We know that the hypothalamus makes something called growth hormone releasing hormone (GHRH), which is in charge of, well, releasing growth hormone. Growth hormone appears to be closely tied to lifespan, so the hypothalamus could be an important control point. One interesting question is how much you can affect the lifespan of a whole organism by just making changes to the brain.

Role of the brain in longevity#

The nervous system plays a role too. Zhang et al. (2017) found that the hypothalamus’ neural stem cells (NSC) secretes small pieces of RNA in vesicles (exosomal miRNA), and their rate of release decreases with age.

Note that for a while it was thought that there were no stem cells in the brain and thus no renewal of neurons. Now we know that in some select areas of the brain there are some, so far they have been found in the hypothalamus both in mice and humans (Pellegrino et al., 2018)

Using a virus to remove a few of these NSCs, or implanting NSC into mice the lab showed a decrease in lifespan after removing these cells (In mice 250 days old), and conversely an increase when implanting them (In mice 600 days old), in this latter case extending maximum lifespan by around 13%.

It has also been found that the genes coding for certain proteins (REST) related to neural activation are more expressed in brains of long lived individuals. Genetically engineered worms with lower activity of REST live shorter lives, and in mice increased REST seems to activate FOXO1, a transcription factor that has elsewhere been found to delay aging.

Tricking mice into thinking that they are colder than they are also has positive effects (Conti et al., 2006): raising the temperature of the hypothalamus tricks it into thinking the whole body is warmer, and the hypothalamus tries to compensate by, seemingly, making cells more efficient and thus generating less heat. This increases median lifespan by 12-20% (male/female) in mice, but does not extend maximum lifespan.

Chemistry of ageing#

As JPM noted, the number of longevity drugs is growing exponentially.

In experiments on chemical modulation of ageing, it is important to check that effects are robust against different common conditions and strains. Moreover, it needs to be established that the effects truly arise from the administered drugs. For example, the effect should not be due to an indirect dietary restriction effect because animals eat less food containing the drug which might be perceived as distasteful or toxic.

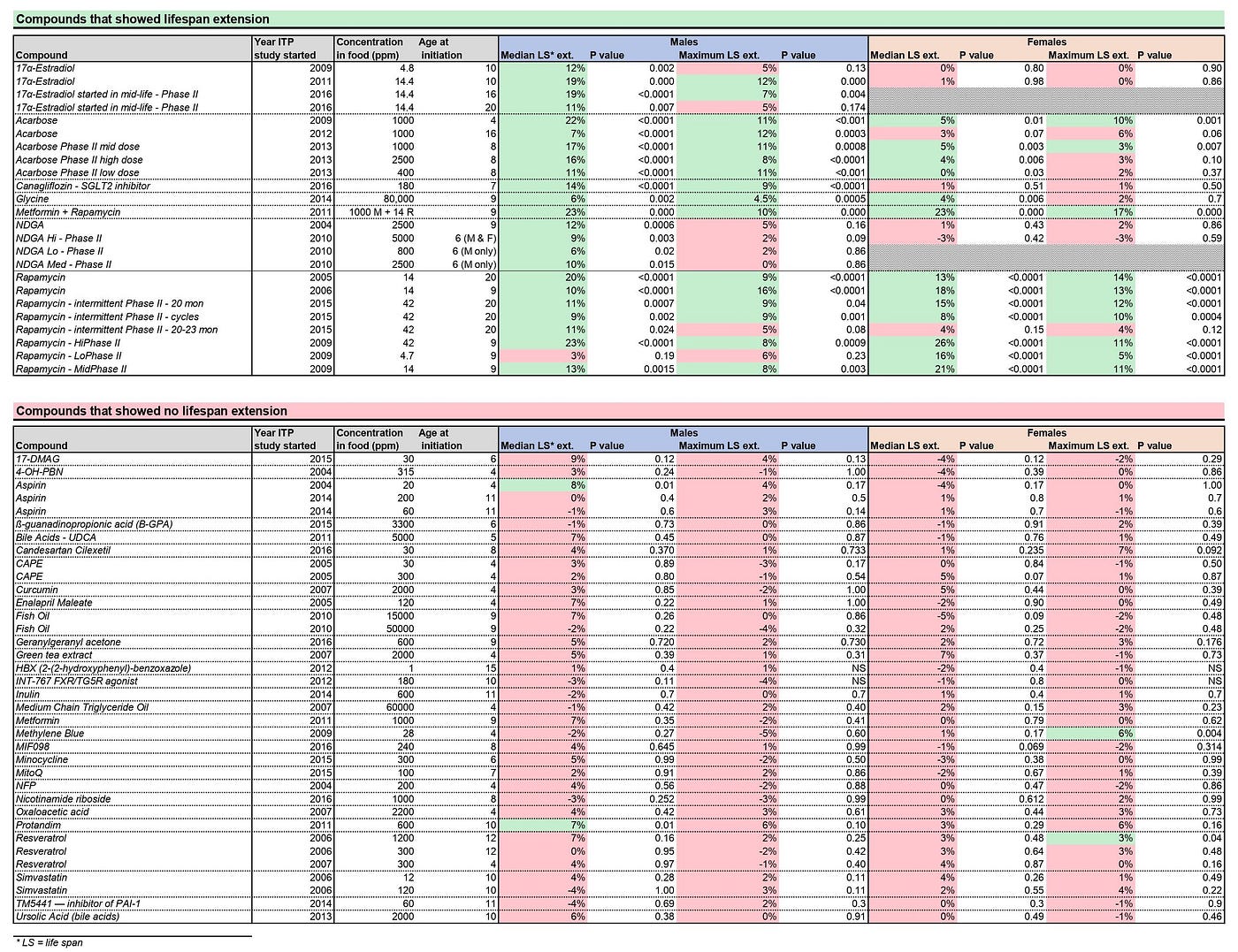

In order to test these drugs we need a standardised protocol. Almost 20 years ago, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) via the National Institute on Aging (NIA) rolled out the Intervention Testing Program (ITP), a multi-institutional study investigating treatments that extend lifespan in mice.

The ITP is an attempt to standardize and simplify not just how we measure the effects of these interventions on mice, but also what we measure. Sometimes, researchers run dozens of tests and try dozens of metrics with the goal of obtaining a positive result that they can publish to great fanfare. The ITP, on the other hand, was designed to provide an answer to one simple question: does the intervention extend lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice? And since a major goal of the project is to provide critical tests of anti-aging approaches, all data is published, including negative results.

Aging has the NIA Interventions Testing Program, or ITP (Nadon et al., 2017) where they test the same thing in three labs with larger sample sizes and rigid experimental protocols. Their stage one uses around 100 mice per group, while their more rigorous second stage tests use up to 500 mice across all the labs per group. This testing has revealed as of 2017 six compounds that extend life in mice. Some of them only worked on males, others on both male and female mice, and in those the effect by gender were different. Consult this source for a more comprehensive overview.

Note that one should be careful about the potential side effects and only optimizing for maximum lifespan does not seem smart.

Studies with longevity effects limited to ITP outcomes:

Rapamycin [As noted in pathways of aging chapter.]

Acarbose [David E Harrison, et.al. Acarbose improves health and lifespan in aging HET3 mice]

Vitamin D [Karla A. Mark, et.al. Vitamin D Promotes Protein Homeostasis and Longevity via the Stress Response Pathway Genes SKN-1, IRE-1, and XBP-1]

Aspirin [Only in males did it improve median lifespan]

Canagliflozin [another anti-diabetic drug similiar to Acarbose]

17-α Estradiol [weak estrogen and a potent 5-α reductase inhibitor, 17-α estradiol has been shown to improve metabolic function, enhance insulin sensitivity and reduce fat and inflammation in old male mice without causing feminization]

Senolytics- senescent cells accumulate and this is negative due to the SASP, let’s just get rid of them.

Sirtuin activating compounds (STACs) - general category, under which resveratrol fall under, they are usually paired with NAD boosters (Most commonly, nicotinamide riboside (NR) less commonly nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN)), to get extra NAD+ to fuel the increase in sirtuin activation.

Studies that failed ITP outcomes:

Metformin [As noted in pathways of aging chapter.]

Resveratrol [Islam MS, et al. Effect of the Resveratrol Rice DJ526 on Longevity.]

Nicotinamide Riboside [ precursor to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), a ubiquitous molecule that mediates energy production in cells.]

A very extensive pharmacological perspective on targeting aging mechanism can be found here.

Parabiosis#

This (Eggel and Wyss-Coray, 2014) is probably one of the most well known, due to the peculiarities of the process involved: It consists of transfusing blood or plasma from younger individuals to older ones, this in particular is known as heterochronic parabiosis (Ludwig & Elashoff, 1972), to distinguish it from cases where the animals are the same age. In early experiments, this was done by fusing the circulatory systems of two mice of different ages.

Later, in 2005 and then 2011, other experiments with a similar design showed that the older mice of the pair showed improved tissue regeneration, heart function and cognitive performance, while the reverse was observed in the younger mice. The reason this was happening is that there are proteins or other elements in the bloodstream of old mice that are harmful in higher concentrations like CCL11 while others that are beneficial are reduced in amount (Conese et al., 2017)

Of course, we all wonder if this work in humans. The TV series Silicon Valley made popular the concept of blood boys, which ended up being memed into reality by real-life startup Ambrosia, who provided plasma transfusions from young donors. They claimed it had benefits for their patients after a trial, but they never released any data, and the after the FDA issued a warning saying that the treatment is not effective, they temporarily closed down, but they have since resumed business.

There is no evidence indeed that this works in humans, but there are ongoing trials to see if it does work. The one I could find is the PLASMA (Plasma for Alzheimer Symptom Amelioration) study at Stanford. So far they have merely done an RCT in a very small sample (9 people per group) to prove that the procedure is safe (Sha et al., 2019). This all sounds somewhat disappointing, especially given that the study was completed in 2017 and back then it was reported that in that same data there was no improvement in alzheimer. This work seems to have done in part by Alkahest, a company founded by Wyss-Coray.

More recently, Horvath et al. (2020) showed that more extensive replacement of blood plasma (Rather than joining mice, infusing them with a proprietary plasma formula every few days) leads to improvements across the board with the exception of the brain. The authors speculate that this may be because

This, of course, raises a related and equally interesting question, which is why does plasma fraction treatment not reduce brain epigenetic age by the same magnitude as it does the other organs? We can only begin to address this question after having first understood what epigenetic aging entails. As it stands, our knowledge in this area remains limited, but it is nevertheless clear that: (a) epigenetic aging is distinct from the process of cellular senescence and telomere attrition 41, (b) several types of tissue stem cells are epigenetically younger than non-stem cells of the same tissue 42,43, (c) a considerable number of age-related methylation sites, including some clock CpGs, are proximal to genes whose proteins are involved in the process of development 44, (d) epigenetic clocks are associated with developmental timing 22,45, and (e) relate to an epigenomic maintenance system 20,46. Collectively, these features indicate that epigenetic aging is intimately associated with the process of development and homeostatic maintenance of the body post-maturity. While most organs of the body turn-over during the lifetime of the host, albeit at different rates, the brain appears at best to do this at a very much slower rate

We don’t know what their proprietary formula is, but perhaps it’s just (or mostly) fresh albumin. Most circulating proteins are albumin, so getting that fixed is a large leverage point. There have been preliminary trials in humans showing cognitive benefits of infusion with fresh albumin (Loeffler, 2020) and work relating the oxidization of albumin to aging (Luna et al., 2016) exists.

On the other hand, the Conboys have also two recent papers (Mehdipour, 2020; Mendipour, 2020) where they merely dilute the plasma, replacing plasma with fresh albumin. The interpretation of the paper is that diluting “junk” that’s present in blood is beneficial and they try to justify that it is not the additional albumin they are adding, but they don’t go as far as claiming that the albumin has no effect (“Ectopically added albumin does not seem to be the sole determinant of such rejuvenation”).

Both the SENS foundation and Eli Dourado take these results to imply that the benefits from parabiosis / plasma exchange are not due to anything beneficial being present in young blood, but rather to the accumulation of “junk” in old blood. SENS does point to a bunch of specific cases where putative “young blood factors” turned out to be not so, ultimately GDF11 when tested on on lifespan has no effects. But they don’t point to a study where they tried to inject young blood to old mice or other models; after all it is perfectly possible that GDF11 is not effective yet something else is. The only such study I could find was Shytikov et al. (2014) where they injected young blood plasma to old mice, finding no lifespan effects. The bulk of the evidence then points to dilution being a robust effect whereas we have not identified any specific factors in young blood that can induce rejuvenation. What then, is in Horvath’s mysterious proprietary Elixir? Whatever is it, it doesn’t have to be -nor they claim it to be- based on or inspired by, young blood factors. They have just shown that there are injections one can administer that cause systemic rejuvenation effects.

Drug combinations and repurposing#

After reading the above, you probably thought: Hey, shouldn’t we just try everything at the same time and see what happens? Indeed this seems to work.

We said that metformin doesn’t seem to do much and that rapamycin does. But what if you combine the both? Well, rapamycin leads to 10-13% longer median lifespans in mice at 14 ppm. Combined with metformin (1000 ppm), that goes up to 23%, even when metformin on its own had no effect (Strong et al., 2016). It reminds to be seen, however, what happens with the high dosages of rapamycin than on its own are already able to achieve similar effects.

In flies, a combination of rapamycin, trametinib, and lithium extended their life by 48%, which is more than the sum of the effects of each of them(Castillon-Quan et al., 2019).

In worms we already knew that certain mutations along the mTOR or IIS pathways can make worms live substantially longer. But what if we create a super-worm with many of them? Yes, they live longer (500% more) than what one would expect from the sum of the effects alone, report Lan et al. (2019), though again this same combination is unlikely to have as large effects in longer-lived species.

This doesn´t mean that every combination is good. A recent study (Palliyaguru et al., 2020) showed that combining a STAC with metformin reduces longevity even when, in that study, metformin on its own has no effect and the STAC increases median (but not maximum) lifespan. More work is needed to determine exactly when drugs conferring putative longevity benefits will lead to synergies or the opposite.

One of the key selling points to repurposing drugs for aging is that the barier of (FDA) aproval is much lover. Since there drugs have already passed these tests. For the theory and the computational aspect of drug repurposing please refer here.

Partial reprogramming#

Idea is that with four transcription factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, C-Myc), aka OSKM factors or Yamanaka factors, that can transform any cells back into stem cells. With that essentiall rejuvenating the cell, tissue and the organ. So the epigenome gets damaged over time. But we also know that somehow it gets more or less reset (Not perfectly, this is why transgenerational epigenetic inheritance is a thing) when the zygote forms (Rando & Chang, 2012 so there should be a way to take a cell and reset it. Back in 2006, Shinya Yamanaka showed that one could take a random cell, make it express four genes (The initials of which are OSKM, or elsewhere known as Yamanaka factors) and make that aged old cell into a fresh and young stem cell.

Now, if you just did that to an organism it would become a blob of stem cells, and indeed something like this is what happens if one happily forces expression of OSKM in mice, one gets cancer and teratomas. But what if instead one goes only halfway? Using genetically engineered mice that express OSKM only when dosed with the antibiotic doxycycline, and having the mice on and off that drug, Ocampo et al. (2016a) rejuvenated and extended the lifespan (maximum by 20% and median by 33%) of genetically engineered mice that show premature aging. Seeking a less carcinogenic combination of factors, the Sinclair lab (Yuancheng et al., 2019) tried just OSK in the eye of mice to see (no pun intended, I promise) if they could regenerate the optic nerve after an injury, and restore vision in mice. And they did it.

There are many ways to reprogram cells: Some are “integrating” (They cause permanent edits in the genome) like various kinds of virus, while others are temporary, like plasmids, adenoviruses (Unlike other virus, these just inject their DNA into the cell to replicate, rather than changing the host’s DNA), proteins or small molecules. The best one in terms of efficiency and not being permanent is the Sendai virus; which however is expensive and hard to produce (Ocampo et al., 2016b).

Oddly, senescent cell’s SASP make it easier for neighbouring cells to be reprogrammed, so perhaps reprogramming followed by senolysis would have synergistic effects (Ofenbauer & Tursun, 2019).

For a great detailed overview have a look here. Or a recent paper here. Tackling this problem with machine learning is already underway and companies are trying to find novel factors and their combinations that could make a difference.

Note that combining multiple therpies might even have better effects: Combining Stem Cell Rejuvenation and Senescence Targeting to Synergistically Extend Lifespan

Environmental effects on ageing#

The idea behind investigating these and other stresses like irradiation, low or high oxygen environments or other chemical stresses, is that low doses of otherwise harmful conditions might trigger adaptive responses which improve the functional ability, a concept called hormesis. And vice-versa.

Ambient temperature [Conti, B. 2008 Considerations on temperature, longevity and aging.]

Cold stress [Le Bourg, E., Massou, I. & Gobert, V. 2009 Cold stress increases resistance to fungal infection throughout life in Drosophila melanogaster.]

Microgravity in space-flight and hypergravity in centrifugal systems [Le Bourg, E. 1999 A review of the effects of microgravity and of hypergravity on aging and longevity.]

Sleep [Cirelli, C. 2012 Brain plasticity, sleep and aging.]

Dietary restriction [Piper, M. D. W., Partridge, L., Raubenheimer, D. & Simpson, S. J. 2011 Dietary restriction and aging: a unifying perspective.]

We have classified interventions broadly based on the 3 classes. Another prelevant approach is to think about the hallmarks of aging. These are general, cell based observations, that overlap with the previously defined classification.

Alternative aging interventions#

Going through old, not necessarily well-known experiments to see if there are opportunities is something I don’t believe is being done that often, and is probably an unusually good place to apply a little bit of time and attention for big returns.

That said, let’s look at some specific examples! These are all results from prior to the year 2000, that are experimental interventions affecting vertebrate lifespan or aging, and which aren’t currently the focus of a research program that I’m aware of.

Lowering Body Temperature: 71% Life Extension in Fish

Unusually long-lived vertebrates (tortoises, sharks, rockfish, etc, which can survive for centuries, or naked mole rats, which are extremely long-lived for their size) are frequently cold-blooded. Warm-blooded animals which are long-lived (in absolute terms, like whales, or relative to their size, like bats, hummingbirds, and squirrels) often undergo temporary reductions in body temperature, during diving or hibernation. Moreover, interventions like dietary restriction which extend lifespan have the effect of reducing body temperature. So can reducing body temperature directly extend life?

For a cold-blooded example, transferring fish from 20-degree water to 15-degree water extended lifespan by 71%, in a 1972 study. Liu, R. K., and R. L. Walford. “The effect of lowered body temperature on lifespan and immune and non-immune processes.” Gerontology 18.5-6 (1972): 363-388.

To reduce the body temperature of a warm-blooded animal, it’s not enough to reduce ambient temperature, since warm-blooded animals generate heat to compensate. In fact, reducing the ambient temperature actually shortens mouse lifespan. However, there are tricks to lower body temperature in a warm-blooded animal.

Mice genetically modified to overexpress the uncoupling protein, UCP2, in the hypothalamus have lower body temperature than wild-type Conti, Bruno, et al. “Transgenic mice with a reduced core body temperature have an increased life span.” Science 314.5800 (2006): 825-82, and they live longer than their wild-type counterparts (20% increase in female median lifespan, 12% in male.)

You can also induce hypothermia by stimulating the heat-detecting cells in the hypothalamus, either by injecting capsaicin Jancsó-Gábor, Aurelia, J. Szolcsanyi, and N. Jancso. “Stimulation and desensitization of the hypothalamic heat‐sensitive structures by capsaicin in rats.” The Journal of physiology 208.2 (1970): 449-459., heating the hypothalamus directly with a thermode Hammel, H. T., J. D. Hardy, and MiM Fusco. “Thermoregulatory responses to hypothalamic cooling in unanesthetized dogs.” American Journal of Physiology-Legacy Content 198.3 (1960): 481-486., or stimulating the heat-sensing neurons optogenetically Zhao, Zheng-Dong, et al. “A hypothalamic circuit that controls body temperature.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114.8 (2017): 2042-2047.

The natural next experiments to do are a.) see if any of these other methods of inducing hypothermia affect lifespan and diseases of aging in mice or other mammals; b.) do longitudinal transcriptomics or other broad assays to see what reduced body temperature is doing and whether its effects can be simulated chemically or genetically.

Altered Photoperiod Cycle Length: Short “Years” Shorten Lifespan 30% in Lemurs

Days get longer in summer and shorter in winter; by lengthening or shortening the cycle of alteration in photoperiod length (by changing artificial lighting) you can give an animal a shorter or longer subjective “year”. This turns out to affect lifespan!

The gray mouse lemur is a prosimian primate, native to Madagascar, that is long-lived for its size. During the long-day summer, gray mouse lemurs breed and are more active; during the short-day winter, they gain weight, become lethargic, and don’t copulate. If you alter the photoperiod cycle artificially, you can alter the timing of these behavioral and morphological changes accordingly – and if you reduce the “year length” by a third, from 12 months to 8 months, lifespan also shortens by 30% and the onset of white fur happens 30% earlier. Perret, Martine. “Change in Photoperiodic Cycle Affects Life Span in a Prosimian Primate (Microcebus murinus.” Journal of biological rhythms 12.2 (1997): 136-145. . In other words, lemurs live 9-10 “subjective years”, whether those are 8-month years or 12-month years.

The obvious follow-up experiment is to go the other direction – do lemurs (or other animals) live longer if you subject them to 16-month subjective years? And to take some tissue and blood samples and try to identify how this effect works – do we see pathological changes, transcriptional changes, hormonal changes, metabolic changes?

Constant Light Exposure: 25% Life Extension in Hamsters

A Syrian hamster model of congenital heart disease showed delayed onset of heart failure and 25% life extension if they were kept in continuously lit conditions. Tapp, Walter, and Benjamin Natelson. “Life extension in heart disease: an animal model.” The Lancet 327.8475 (1986): 238-24 The obvious corollary studies are to take heart tissue samples and blood samples and look for altered gene expression or metabolic parameters that might explain the effect of light exposure on preventing heart failure. It also might be possible to experiment directly with continuous light exposure on humans, since it’s probably not dangerous.

Pineal-Thymus Graft: 24% Life Extension in Aged Mice

Implanting the pineal gland of a young mouse into the thymus of an old (16-22 month) mouse extends lifespan 19% in C57BL6 mice, 20% in Balb/c mice, and 35% in hybrid mice, for an average of 24% overall. Pierpaoli, Walter, et al. “The pineal control of aging: the effects of melatonin and pineal grafting on the survival of older mice.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 621.1 (1991): 291-313. This is consonant with a more extensive literature about the pineal gland or the main hormone (melatonin) it secretes having a life-extending effect through preventing the dysregulation of the circadian rhythm which occurs with age. The obvious follow-up study to do is a replication of the same implantation experiment, along with longitudinal expression data, to find out how this works and work towards identifying how a similar effect could be replicated by a less invasive intervention.

Splenectomy: 19% Life Extension in Aged Mice

In a 1969 experiment, adding spleen cells to mice of the same age as the cell donors shortened lifespan; adding spleen cells from younger mice (14 week) to older mice (76 week) extended median lifespan from 105 weeks to 128 weeks, a 13% lifespan effect; and removing the spleens of mice altogether at age 97 weeks increased median remaining lifespan from 118 to 158 weeks, a 19% lifespan effect.

Clearly, the aged mouse spleen contains some factor that accelerates age-related decline. The obvious question is to find out what this is, through expression or proteomics studies on young, aged, and splenectomized mice, and see if there’s a way to target the culprit pharmacologically.

Induced Hypothyroidism: 17% Life Extension in Rats

Exposing newborn rats to thyroid hormone permanently reduces their bodyweight and thyroxine levels; it’s a way of artificially inducing hypothyroidism. Ooka, Hiroshi, Saori Fujita, and Emiko Yoshimoto. “Pituitary-thyroid activity and longevity in neonatally thyroxine-treated rats.” Mechanisms of ageing and development 22.2 (1983): 113-12 It also has the effect of dramatically elevating their prolactin levels; as prolactin is stimulated by TSH release from the hypothalamus, clearly neonatal T4 exposure doesn’t prevent TSH release in the brain, but rather impairs the thyroid’s ability to respond to it. This induced hypothyroidism also extends median lifespan by 17% and maximal lifespan by 6%. Obviously, inducing hypothyroidism isn’t a viable intervention for humans, but looking at changes in hormone levels and gene regulation in induced hypothyroidism might give clues to what downstream mechanisms are responsible for the lifespan increase and whether there’s a less-side-effect-heavy way to induce it.

Castration: 17% Life Extension in Rats

Removing the testes of male Wistar rats has been found to extend lifespan 17% relative to unbred intact males; removing the ovaries extends lifespan 29% relative to unbred females. Asdell, S. A., and S. R. Joshi. “Reproduction and longevity in the hamster and rat.” Biology of reproduction 14.4 (1976): 478-480. This isn’t too surprising given that caloric restriction (a reliable life-extending intervention in rodents under typical lab conditions) has antigonadal effects, and that extremely dramatic lifespan effects can come from removing the germ cells in C. elegans. Hsin, Honor, and Cynthia Kenyon. “Signals from the reproductive system regulate the lifespan of C. elegans.” Nature 399.6734 (1999): 362. There’s also some correlational evidence – for instance, castrated male cats arriving at veterinary hospitals lived 67% longer than intact males.Hamilton, James B. “Relationship of castration, spaying, and sex to survival and duration of life in domestic cats.” Reproduction and aging. New York, NY: MSS Information Corporation (1974): 96-115.

Obviously, castration isn’t a practical intervention for most humans, but it’s possible that there’s some downstream effect that doesn’t alter fertility or observable sex characteristics and preserves some of the anti-aging effect; this is a good opportunity for looking at longitudinal expression changes in castrated vs. intact animals and trying to identify the mechanism of lifespan extension.

Lateral Hypothalamic Stimulation: 5% Life Extension in Aged Rats

Stimulating the lateral hypothalamus is pleasurable, and animals given the opportunity to self-stimulate will do so; this is what’s known as wireheading. Interestingly enough, there are interactions with aging here as well. Young adult rats have more neurons and more electrical activity in the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA) than old rats; young rats also exhibit more self-stimulatory behavior than old rats when given access to a button that turns on the electrode. Moreover, in old rats, chronic stimulation in the LHA extended lifespan from 1075 days to 1125 days (5% of total median lifespan, 8% of total maximum lifespan, 35% of residual lifespan); stimulation reduced body mass as well. Frolkis, V. V., et al. “The lateral hypothalamic area: Peculiarities of aging and the effect of chronic electrical stimulation on the lifespan in rats.” Neurophysiology 32.4 (2000): 276-282. Is this just a dietary restriction effect, or is it something else? The natural thing to do is to try the experiment again, this time compared against controls given the exact same amount of food to eat; and also, to take brain samples after death and possibly other blood samples during lifespan to try to identify metabolic or regulatory changes caused by the stimulation.

Blindness: Increases Survival in Rats

Blindness affects the circadian rhythm; it effectively gives the same hormonal signals as perpetual darkness. Rats blinded at 25 days had increased lifespan relative to controls; at 748 days, when the experiment concluded, the blind rats had a 95% survival rate while the control rats had a 50% survival rate. The natural follow-up is to do a full lifespan study so we can get an actual measurement of the effect on median lifespan, as well as measurements of other biomarkers so we can identify a mechanism and possibly a way to replicate the anti-aging effect without actually inducing blindness.

Fetal Hypothalmic Graft: Restores Fertility and Circadian Rhythm in Rats and Hamsters

In keeping with the pattern of neuroendocrine effects on aging, it turns out that transplanting the suprachiasmatic nucleus (the part of the hypothalamus responsible for entraining the circadian rhythm in response to day length) from fetal animals into the brains of aged animals can restore the periodicity of the circadian rhythm and restore diminished fertility. With age, circadian rhythms become less regular; animals wake more during the periods when they should be sleeping, and/or are more lethargic during the periods when they should be awake. Fetal SCN grafts reverse this phenomenon in both hamsters Viswanathan, N., and F. C. Davis. “Suprachiasmatic nucleus grafts restore circadian function in aged hamsters.” Brain research 686.1 (1995): 10-16. and rats. Li, Hua, and Evelyn Satinoff. “Fetal tissue containing the suprachiasmatic nucleus restores multiple circadian rhythms in old rats.” American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 275.6 (1998): R1735-R1744. Moreover, 7 of 10 aged rats given fetal anterior hypothalamus transplants regained fertility and fathered a total of 106 pups Huang, H. H., J. Q. Kissane, and E. J. Hawrylewicz. “Restoration of sexual function and fertility by fetal hypothalamic transplant in impotent aged male rats.” Neurobiology of aging 8.5 (1987): 465-472., while medial basal hypothalamus transplants from rat fetuses into aged female rats reversed hypogonadism. MATSUMOTO, Akira, et al. “Recovery of declined ovarian function in aged female rats by transplantation of newborn hypothalamic tissue.” Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B 60.4 (1984): 73-76

The hypothalamus regulates a variety of hormonal signals, which become dysregulated with age; it seems that some of these effects can be reversed by transplanting a younger hypothalamus. The most natural question to ask is, first, does this extend life? Second, can we identify on the genetic or molecular level what the younger hypothalamus tissue is doing that improves aging-related phenotypes? If so, there might be a non-invasive way to replicate the effect.

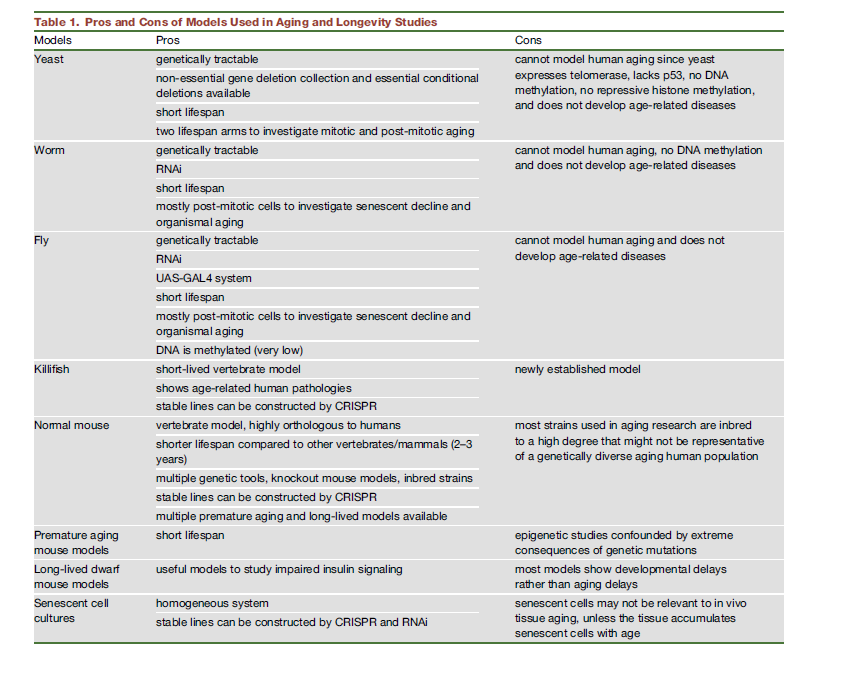

Model organisms for research in ageing biology#

What should be the criteria for choosing a animal model in longevity research and how do we make sure that results on animal models transfer to humans?

lifespan length?

genetic similiarity?

cost of keeping?

etc

Another important question is that aids in this decision is:

How can you efficiently test lots of drugs for their effect on lifespan?

For that, you need a short-lived model organism and a low cost per experiment enabled by automation.

The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the worm Caenorhabditis elegans, the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, the mouse Mus musculus. The common maximal lifespan of these model organisms under laboratory conditions follow roughly a rule of 3 (3 days, 3 weeks, 3 month, 3 years). Usually only findings supported by more than one invertebrate model are evaluated in mice, with the ultimate goal of gaining knowledge about human ageing.

But are mices or worms the optimal model?

They both have their tradeoff. Most drugs that “work” in mouse experiments don’t go on to succeed in human clinical trials. Reference, and all of these are drugs that have been found efficacious in animals, so successful animal studies are very far from a guarantee by themselves.

Check here for a detailed exposition on faulty assumptions beeing made when using mice as a model.

What abour worms, what are the odds of success in mammals if the drug works on worms?

Of course, extending life in a worm is no guarantee of extending life in other organisms. How likely is that? We have no exact measurement, but we do have the DrugAge database of compounds that have been found to extend life in various species. 7% of the drugs listed as extending life in nematodes have also been found to extend life in mammals. This is, in fact, an underestimate, since the majority of drugs tested in worms were likely never tested on mammals (given the high cost and relative rarity of mammalian lifespan experiments.)

Combining these two facts, we can get a rough estimate of 0.35% probability that a compound with mammalian bioactivity, tested on nematodes, will extend life in mammals. In other words, screening 6000 new drugs in worms will yield, in expectation, 300 hits for life extension, of which we expect 21 to also extend life in mice.

Of course, in real life, we can’t do 300 separate mouse lifespan studies. What we can do is take those 300 primary hits in worms, and narrow them down to a more tractable set by doing more invertebrate studies – selecting for drugs with consistent effects across different worm strains and experimental conditions as in the CITP, selecting for drugs that also modify healthspan and other aging-related phenotypes, and running validation assays to select for drugs with biologically plausible mechanisms of action (such as altering transcription or activation of known aging-related pathways, or clearing senescent cells.) Applying these more stringent filters, we could get a “top-15” list of candidate drugs worth testing in mammals. And even if (to be quite conservative) these secondary filters don’t allow us to improve _at all _on the 7% transferability rate at baseline, we’ll _still _expect that on average at least one of these drugs will extend life in mammals.

Research on the mechanisms that drive aging and potential therapies to slow or reverse it is usually done on a series of animal models: yeast, flies, worms, and mice. As mentioned above, the pathways involved in aging are more or less preserved across species, but there are substantial differences that one has to be aware of that can cause a treatment not to work in humans.

Take telomerase. It’s not active in most human cells, but in mice it is (Shay & Wright, 2019). Or cell replication. Cells replicate in humans (Well not always, heart cells do not), and in any given point we have different numbers of cells. But not in the worm C. Elegans, which has around 1000 cells and that’s it. Mice tend to be overweight, which can confound the effects of some interventions like calorie restriction. In general, non-vertebrates do not present senescence, stem cell exhaustion, immunosenescence, or inflammation. (Singh et al. 2019).

There is a paper, Liao et al. (2010) that claims that CR has negative effects in some strains. However upon closer examination this doesn’t seem robust: There were 5 mice per strain, and some of the more extreme negative results recorded involved just 2 or 3 mice (because they couldn’t get enough). In contrast, I couldn’t find any papers with a larger sample size showing negative effects of CR in mice in lifespan. To be sure some papers show neutral effects (no increase in lifespan). There are some cases, like in DBA mice where CR of 40% started early in life increases early mortality. The net effects seem neutral (eary mortality+lifespan increase for the individuals that survive). 40% CR is quite extreme; people that do chronic CR rarely go this far. More recently, Unnikrishnan et al. (2021) repeated Liao’s analysis with a larger sample (though, perhaps, not large enough!) with the expected results: Liao had found a worst case scenario of the 115-RI mouse line where lifespan went down by 70%, Unnikrishnan et al.’s sample increased their lifespan instead as the model would predict, though this effect was markedly stronger in females than males. Interactions between genetic background and the effects of CR are real, but the reasons to be pessimistic are not as strong as one may infer from Liao’s paper.

Is there any other promising animal model alternatives?

Derived from the table and taken from here, question is: “What model is the most suitable for longevity research”

Save time: Conveniently, Daphnia live on average only 30 days. Moreover, for some interventions there is a chance to reduce the duration of the experiment to a couple of hours: apply the drug at a high dosage and immediately observe the behavioral change. But in order to judge the accuracy of accelerated approach, it is necessary to conduct a number of preliminary studies.

Convenient features: Sensitive to drugs. Transparent. Visible heart, macrophages. Clonal. Large progeny. Complete genome: A small 250Mb genome is sequenced, wel annotated and CRISPR-editable.

Aging model: First, daphnia also age (the probability of their death increases with age). Secondly, at least one mechanism associated with aging in daphnia overlaps with other model organisms and even, probably, with humans: a moderate reduction in calories prolongs their life.

Convenient to dose the drug: Studies of drugs in worms use unphysiologically high doses to overcome natural xenobiotic pathways. Flies mainly feed as larva, it is impossible to control the amount of drugs that gets into them. In contrast, Daphnia is sensitive to small concentrations.

Save money: A one liter aquarium can comfortably accommodate 100 daphnia. For comparison, we would place only one fish in the same volume. In addition, very low concentrations of the test substance are sufficient for Daphnia (important for testing expensive drugs, which are typically the new drugs). A bunch of cheap Daphnia in a small volume of drug solution makes the experimentation very economical.

Convenient to evaluate the results: It is enough for us to observe the Daphnia, i.e., their movements (no need to open them up or make molecular measurements). This enables automation and scaling up, using video cameras and image analysis of videos from many tanks in the hands of different teams.

Disclaimer: Even tough its a novel idea, to use daphnia as a default aging animal model, there are three big question marks regarding using Daphnia vs Mice:

What are the effect of the genetical difference?

What are the rffect of the fact that it is not a mammal?

What is the general translatability of the studies?

Conclusive studies need to be conducted before the consensus switches from mice to daphnia as the default animal model of aging.